The role of design

This project had come about through an interdisciplinary or potentially even transdisciplinary collaboration that saw scientists work together with PES scholars using design as the bridging mechanism.

Why design? Well, that is partly to do with a law of the instrument, ‘if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail’ tendency because I (Jo) am a designer! But, it also seemed useful to tackle the ‘persistent gulf between PES [Public Engagement with Science] scholars and scientists communicating with the public’ that Salmon et al. (2017) and others have noted by being sited a little tangentially to science and PES. Design lives outside science and the humanities/social sciences, being what Nigel Cross (1982) describes as a ‘third culture’; a particular way of looking at things that’s different from the established ‘two cultures’, so has a slightly external perspective that I thought could be useful.

A spectrum of approaches

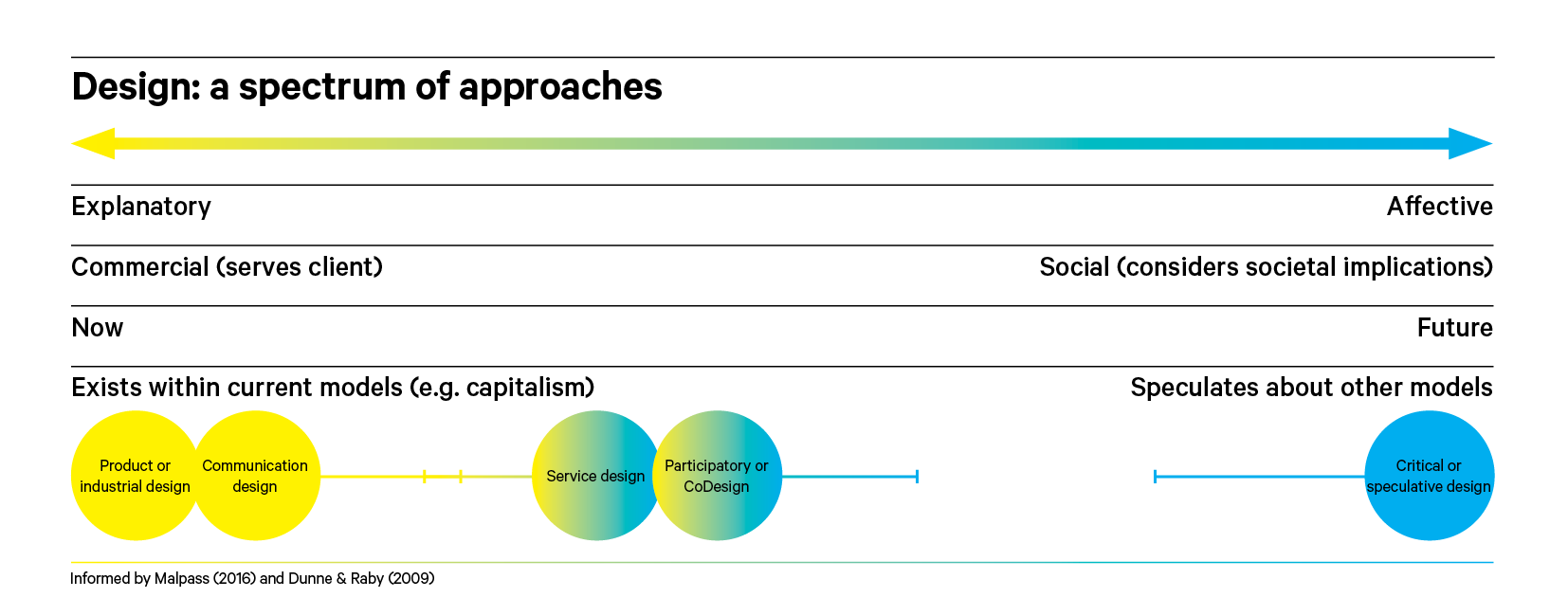

When we talk about design in relation to science communication, the most frequent connection is in the professional visual communication context – clarifying, illustrating (Trumbo, 1999, p. 421); as a translator of information with ‘the potential to increase the attractiveness, understandability, and communication power of research findings’ (Khoury et al., 2019, p. 4). Increasingly, there has been recognition of the visual communication designer as a researcher and practitioner in collaborative, interdisciplinary and cross-cultural research projects, particularly through using a critical position (Dunne & Raby, 2013; Malpass, 2016, 2017; Mazé, 2009; Michael, 2012) to negotiate the science/society interface.

This suggests there is a range of approaches within design — a spectrum — from the explanatory to the affective:

A spectrum of design approaches

My general design practice (as a graphic designer) normally sits at one end of this spectrum, and there are elements of the explanatory visible in the scicomm laundromat — the zine workbook and all the materials have been carefully curated and produced. However, we have nudged at the other end of the spectrum — the speculative end that considers possible futures — using things like ‘design probes’, which deploy open-ended questions to elicit ‘insights into…lives, thoughts, hopes, and fears’ (Boucher, 2018) via informal qualitative responses that might be drawings, statements or stories.

Design processes and scicomm

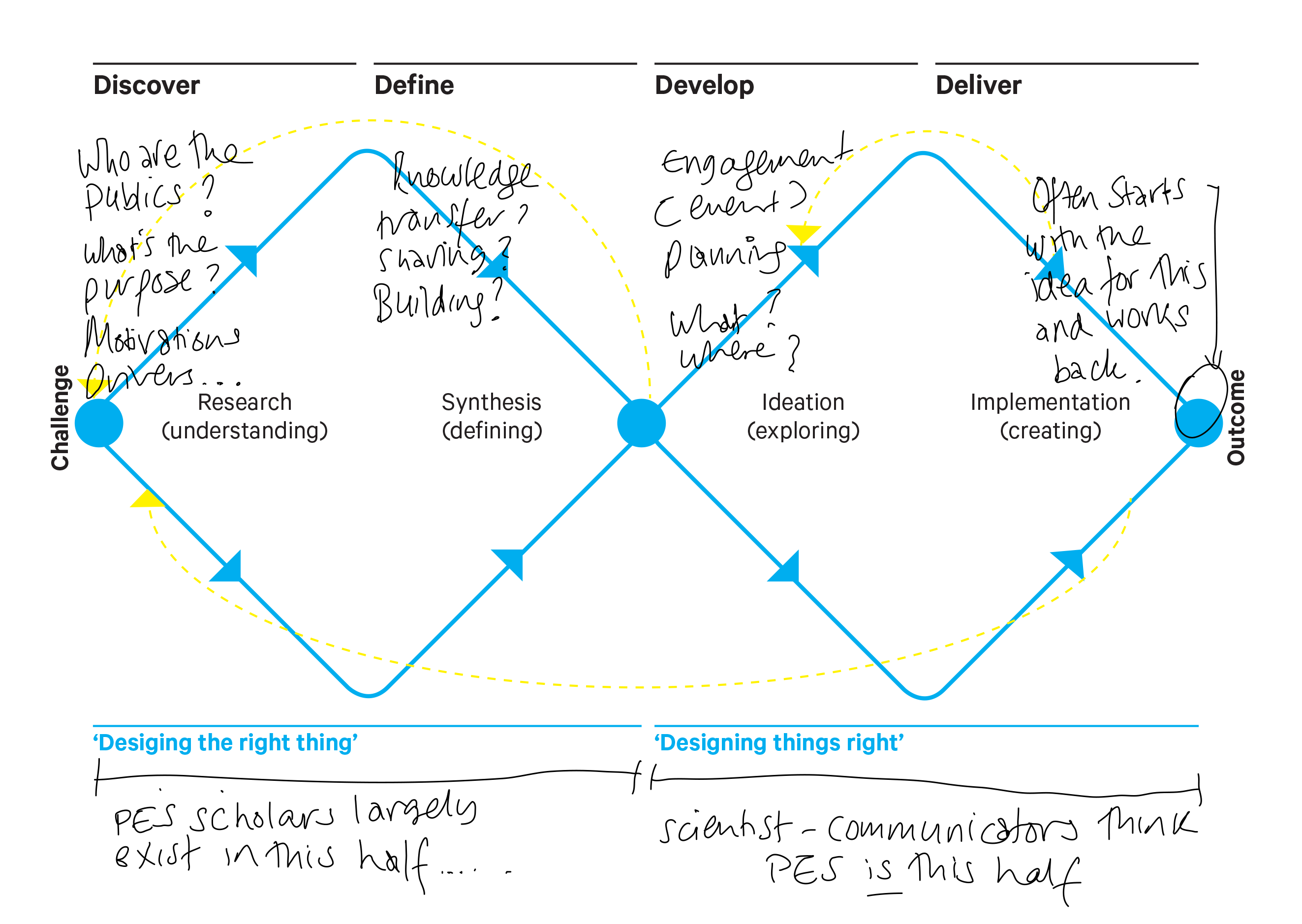

Perhaps the most interesting connection we found between design and scicomm, though, was with the process of design. There are many visual models of design practice. The one below is the UK Design Council's ‘double diamond’. This is a simplified explanation of how design works based on the observation of expert practitioners rather than a ‘map’ or how-to guide to follow, and it does, of course, remove much of the noise and mess that is part of a design process. It also perhaps underplays the fact that there may be many loops back and forward (or repeats of the whole process) in the course of a project.

In essence, it shows a design process articulated as two diamonds: the first is about discovering and defining what the problem is — working out what ‘the right thing’ would be. The second diamond is the development of that thing, and its delivery so that the thing is ‘designed right’. There may be loops at any time in an iterative, repetitive cycle.

I have used this model to think about different stages of my research process (designing a PhD). But we also came to the realisation that it maps well onto what we were observing with science communication too, albeit in a slightly different way. We noted that PES scholars think about the big questions: about publics, the science/society relationship, democracy and power. Scientist-communicators on the other hand, when deciding to do some scicomm/engagement, frequently jump straight to the endpoint of the second diamond and work back to the middle, with the activity largely predetermined.

Part of what we have been doing is thinking about the theory while getting our hands dirty with 'the doing' of running the scicomm laundromat as an engagement activity, and inviting scientist-communicators to peek into the first diamond in order to refine what ‘the thing’ is.

The UK design council's original double diamond with our own annotations

You can read more about our use of design in our JCOM paper, Bailey, J., Salmon, R., & Horst, M. (2022). The ‘Engagement Incubator’: Using design to stimulate reflexivity about public engagement with science. Journal of Science Communication, 21(04), A01. doi.org/10.22323/2.21040201